Ultima VI Decodexed

Some loosely-organized observations on Ultima VI

Some Background

I'm sure that I'm carrying around baggage as a (struggling) game designer. There's a difference between building on— or even duplicating— an existing design, and badly emulating it. The risk for a designer is not so much lack of originality as it is missing the point.

Ultima VI, an RPG released in 1990, produced by Richard Garriott (of Ultima fame) and Warren Spector (of Deus Ex fame) was formative for me in wanting to try and make videogames. Since (whether I like it or not) it occupies a big chamber in the back of my mind, I had better be sure and clearly understand what makes it so compelling. This essay is an effort to do that.

I'm replaying it now, first time in a long time. For my own sake I've been taking notes, deconstructing it just a bit as I go along. In case it might be useful to others, and because I'm interested in additional insights people might have, I'm putting this online.

Note that you don't have to have played Ultima VI at all to read or understand this essay. I hope it has some ideas that could be useful for game design in general.

So if you're interested, let's Journey Onward...

Character (NPC) Connectedness

Brittania, the game world of Ultima VI, weighs in at about 200 characters. Each has a unique portrait, backstory, relationships, house, job, and daily schedule. A cloth-maker in one town might mention that he's not good enough to make silk, but that another cloth-maker (whom he knows by name) lives elsewhere who can. A child mentions that she is named after her aunt who lives far away— and although she doesn't know where "far away" is, you can bet theres an aunt with the same name, in another town somewhere.

One of the central quests revolves around a silver tablet; Mariah at the Lycaeum (a large library) has part of it, which she says she bought from a band of gypsies. But there are two bands of gypsies. They travel from place to place, so you'll only meet them occasionally. Odds are you'll ask the wrong group, because they're easier to find. And yes, this wrong group will in fact tell you a story about the silver tablet, for some money— but it's not the right story! Elsewhere in a tavern, a bard will mention that there are actually two groups, and CLICK! You realize where you went wrong.

This goes on, and on, and on. And it's incredibly engaging.

Pure-keyword Information

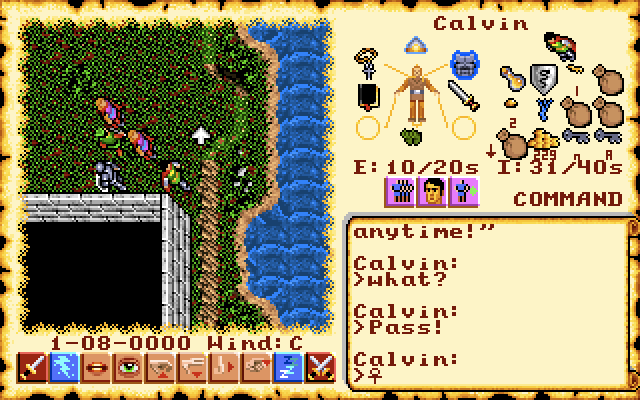

You interact with characters by typing in keywords directly; I'm calling this a pure-keyword system since it's up to you what to type. The game only cares about the first four letters you type, so it's not about simulating conversation. (You don't say, "what's your job?", you just say "job".) The purpose isn't to fool you into thinking the characters are intelligent, or even to let you interact in a "less gamey" natural-language way. It's something else.

Characters are connected via information. The pure-keyword system means everyone could (and often will) have additional backstory or sometimes quest progress accessible if you only know what to ask them.

This is keyword information system is maybe the most central mechanic in the game, and what separates it from simpler "menuable-keyword" systems like in Ultima VII (7) and just about every non-text-adventure videogame since then. To possess useful information as a player, outside of the game itself, is empowering and enjoyable, and being free to type pure-keywords is an ideal solution.

The sensation of making a connection, of something "clicking" is very positive. We often experience this in videogames when solving a puzzle. However, in the case of a puzzle, we're usually held up or prevented from moving on in some way, which carries with it the risk of frustration.

When it comes to making connections between characters in Brittania, though, it's usually incidental.

So, in the process of moving forward on an objective, we will also put together pieces of a puzzle that we didn't even know was a puzzle until we solved it! Kind of lovely.

Another way to create this effect is through environmental storytelling, which is a very popular and developed technique these days. It also plays a (smaller) role in Ultima VI. For instance: why does the fletcher (arrow-maker) have a spool of thread in her shop?

Aside: Why Not Have Keywords in Mobile Games?

I imagine most game designers intuit that players will find it tedious to type keywords in. And in fact, typing is very awkward via a gamepad, so this type of system is probably correctly avoided for most console games (but it does feature in some, e.g., in Animal Crossing.)

However, texting is on the other hand probably the second most common thing we do (after reading) with a smartphone. Something I've thought about for some time now is that this kind of keyword mechanic could work very naturally in a mobile game.

Visibility - Field of View and Flood-filling

Ultima VI uses a fairly interesting and unique visibility system, comprised of two things:

- A narrow field of view.

- Flood-filling to determine hidden squares.

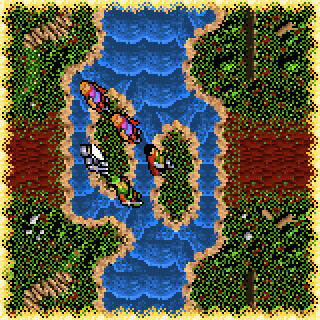

The narrow field of view means the game doesn't show you very much of the world at once-- only about 11x11 squares. There is no minimap to give you a wider sense of where you are, either; apart from one-time-use items and spells you are really limited to seeing this.

Most importantly, though, it uses a flood-fill mechanic-- not line of sight-- to determine what you can and cannot see.

Quick trainer on how a flood-fill works:

- Start with the square where the player is standing.

- Is there a wall or closed door to the north? If not, then it's open-- mark it as "visible"

- Check the other directions, too.

- Now go back to step 1, but instead of the player, do it for all squares currently marked "visible"

- One more thing: if a tile is too far from the player it should never be marked "visible"

More simply, this is called "flood-fill" because we can think of the visibility as flowing like water. If the door to a room is closed, the water can't get in, so we can't see inside.

Likewise, if we're inside that room, we won't see outside— just black tiles. The water stays in, too.

One last thing: we can see into neighbouring rooms, if the door is open or it is connected by a hallway, as long as that door isn't too far away. The water doesn't flow too far, but it does flow from room to room.

Flood-fill vs. Line-of-sight, Intuition of Interior Spaces

Flood-fill visibility might seem unusual; a more logical approach would be to use line-of-sight, i.e., computing a view for the player where their ability to see behind a wall or another object depends on if that wall or object were in front of them. Line-of-sight is done by drawing "visibility lines" radiating out from the player, and stopping where they hit something solid.

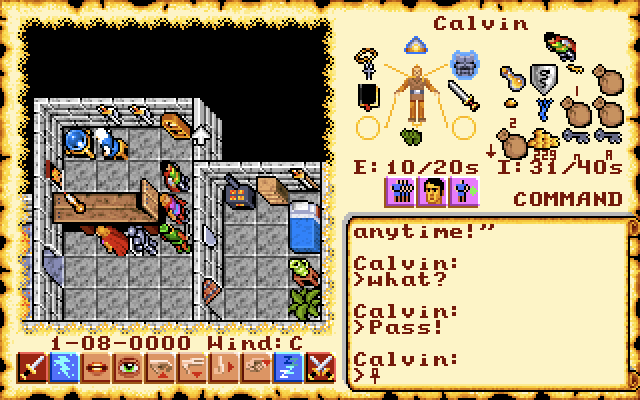

In practice, however, flood-fill has a natural feel to it. For instance when you open the door to a house, you can see all the connected rooms immediately. It gives you the feeling of "entering" the house. And still, if the house has a locked room or closet, it will be obscured.

In a line-of sight system, we would have to explore the house to learn it's layout. This is physically correct in a sense but not really representative of how we experience spaces, especially interior ones. In real life, "the other room" might be actually invisible, but conceptually your mental map of it is undisturbed and seems complete.

In fact, we typically have a very good intuition about interior spaces; enough to have a sense about not only what but who might be in another room (this is why it's so disturbing to learn someone is home, if you didn't hear them come in.) This impression is built on sound, past experience, and other contextual information. For instance: "so-and-so won't be home until 10", "that chair has been moved since I left morning", or "the coatrack is empty."

The flood-fill system in Ultima VI creates this familiar impression both of entering a space and getting an immediate sense for what's there and who is inside, while capturing equally well the feeling of not yet knowing what's behind a closed door.

Aside: Drawbacks to Line-of-Sight

Because they are at odds with our intuition, especially concerning interior spaces, it might be argued that line-of-sight systems are too legalistic for good storytelling.

For the most part, line-of-sight is used in games where core mechanics depend on having only very precisely-defined information; for instance strategy, stealth, or roguelike games.

Since a line-of-sight system will show only a relatively small "active" slice, they almost always compensate by showing the map (usually darkened somewhat) with static objects and scenery where you have previously seen them, to represent your past knowledge of an area. Usually, moving objects such as characters are not shown in this darkened "memory" space (there are a lot of interesting variations on this, though.)

Line-of-sight will always mean we spend time moving around the map just to see what's inside a building, which might be satisfying in it's own way but can be tedious, if our goal is to encourage the player to make higher-level choices like experimenting with equipment or talking to characters.

Second Entrances

Here is a wonderful design trick I haven't seen used elsewhere, at least not in top-down perspective games.

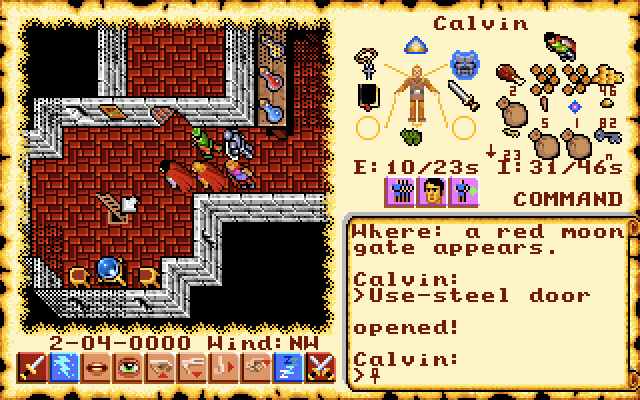

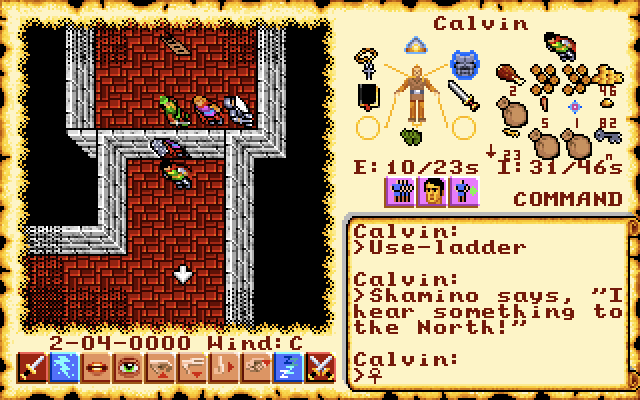

In many cases, underground areas in Ultima VI have a second entrance. So, for instance, we enter the basement of the castle, light a torch, explore for awhile, and eventually find a different ladder up— i.e., we leave by a second entrance.

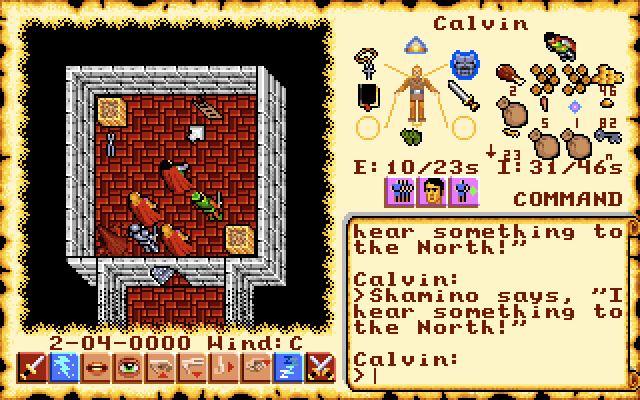

The designers have exploited these second entrances wonderfully through a simple device. Very often, they lead to a hidden room or closet in another building. The effect is that, when we come up the ladder, we might only see one or two spaces around us-- everything else is black. We have virtually no way to know where we are, except that we're in a secret room of some kind, which creates an immediate and overpowering sense of curiousity.

Since the room we end up in is small, we don't have far to look to find the door, though, even if it's hidden somehow.

On opening that door, the flood-fill instantly reveals where we are-- the nearby inn!

Because it's a smaller space to search inside the closet than out of it, it's very likely we were not aware of this secret room before encountering it this way. So most likely we will experience the second entrance in this order, from inside the closet.

Much like the pure-keyword dialog system, learning the location of second entrances which were previously hidden in plain sight is empowering because it's information possessed by the player outside of the game itself.

A similar approach (very commonly used) is to provide "shortcut" mechanics. Essentially, the idea here is that once the player has traversed an area the "long way around" (for instance, made it to the final room in a level), they can open a shortcut that allows them to bypass the challenges they have just overcome. This shortcut could be in the form of a door that only opens from one side (the "far" side, that is) or even as something as simple as adding a beacon to a fast-travel menu.

Shortcuts of this form are a useful design tool but don't really empower the player in the same way that hidden second entrances do, because shortcuts only exist inside the game. Whether they know about the eventual shortcut or not, they will need to reach the end of the level to open it, first.

In most cases, in Ultima VI, we only needed to have known the second entrance was there in order to have accessed it earlier. So they exist not as a game mechanic, as with shortcuts, but as knowledge that the player has outside the game.

Aside: Possibility Spaces

Second entrances in Ultima VI are so effective precisely because they are so well hidden.

If they were easy to find, then the eventual knowledge the player gains of them would not feel significant. Likewise, as mentioned, if they were shortcuts, the player would recognize them as an in-game device, tied to the internal state of the game rather than their own personal memory and experience.

So then, it could be argued, the player's knowledge only has value if they choose to re-play the game, and are able to make use of it the second time around, through by-passing the original route. Otherwise, isn't it functionally the same as a shortcut?

No.

The player's actions will be the same as if it were a shortcut— only accessing the second entrance once reaching it via the primary entrance. How they feel and how they reason about it will be very different.

A prisoner cannot leave their room; a free person will often choose not to. Even over the course of a single day, there is no equivalency in how they feel about their respective situations. What's different is the possibility space— what they could do.

Just as both the prisoner and free person clearly perceive their own possibility spaces, the player will perceive the games', and it will affect how they feel about their experience-- even if their in-game actions would look otherwise the same.

We can stand at the edge of a cliff without going over, or hold an egg without dropping it. Likewise, a pit is still a pit, even if the player jumps over it every time without fail.

This is a central point to game design but it's easy to miss.

Hidden Spaces

Flood-fill visibility has an interesting side-effect. It makes it possible for the designers to create hidden rooms without us being aware of the space they occupy. Walking along the outside back wall of a building, we can see it's shape and roughly it's size-- but the interior is all black because we aren't near any doors. Moreover, we do NOT see any kind of overlay of what we may have seen when we entered the building previously, as we would with a line-of-sight algorithm.

Now let's go in through the front door. As we move to the front of the building, the back part of the building leaves our viewport, so we can't see it anymore. We remember it as a flat wall. Soon, we get close enough (or open) the front door for the flood-fill to show us the inside of the building. Now inside, we walk to the back, and eventually the outside goes black, because the flood fill doesn't reach the front door anymore. And then we see the inside part of the back wall.

What we don't realize is, the back wall we see on the inside doesn't go as far as the back all on outside.

There's a secret room. Because we never see the inside and the outside of the building together, the designers can create "missing space", and use it to place secret rooms, in "plain sight", "past" the end of the building.

This missing space is somemething we occasionally encounter in the real world; one day we might notice that our apartment is actually L-shaped in a spot, and realize that we must in a sense share closet space with the neighbouring apartment. Or, better yet, we find a cubby-hole in an old house after carefully reasoning about the shape of a stairwell or closet, maybe even after we've lived there for some time.

A line-of-sight system wouldn't allow for this, because we'd see both the inside and the outside at the same time. Even though only part of our view would be "active", line-of-sight systems generally need to show us what we saw before, and this will reveal the empty space we haven't yet explored.

@h3 Aside: 2D vs 3D and Immersive Spaces

I want to mention just one more thing about this. In properly 3D games, we don't have any "inactive" part of the map (unless there is a corresponding 2D map, of course.) However, our typical experience in a 3D game is with a different kind of spatial awareness. One advantage of a top-down perspective, even working in 3D, is the intuition we develop about a space. The impression of being physically present is captured differently and in some senses actually better by a top-down schematic than by exploring it in first-person (VR should change this, at least a little, I guess; but then, we don't really move around in VR spaces, yet.)

Some evidence for this: consider that almost all 3D games require a supplementary 2D map to be comprehensible. Without one, it's too easy to get turned around or otherwise lose our sense of direction. Hence the minimap conundrum: the fact that we spend a lot of time looking at the simply-diagrammed minimap in the corner, rather than the detailed 3D view that is supposed to hold our attention.

So an argument can be made that a top-down view can give a more immersive sense of space than even a 3D view, paradoxically, because it lets us form a more intuitive mental model to begin with, and so is closer actually to our real-life experience of spaces.

Narrow Viewport Size, Hand-Drawn vs Auto-Maps

The viewport size is remarkably narrow: only 9x9 squares or, if you count the partially viewed edges, 11x11.

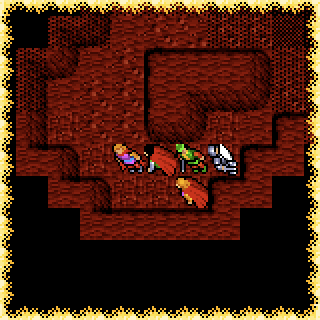

This works well in certain contexts. In dungeons, it encourages us to draw maps on paper, which is very enjoyable (but requires some discipline.) Again, this is really about the empowerment of gaining useful information outside of the game (your notes sit on your coffee table, and are indespensible, so it's empowering to make and to use them.)

Without a hand-drawn map, it's very difficult to remember the layout of twisty-passaged dungeons since we never see very much of them at once. In fact in the underground areas, drawing maps is a necessity: without them we'll probably start to feel quite lost. The dungeons are often laid out carefully and logically, so a map can help us formulate a good navigation plan. The difference between taking a right hand turn here, versus a little ways further down this hall, can be very large. So the process of drawing the map is enjoyable, since we're gaining some agency over our situation.

The risk, of course, is that the player won't want to draw a map by hand. In this case, any cleverness or larger plan to the dungeons will probably be lost, and they'll just wander aimlessly. One way to mitigate this is to draw the map for the player, as they explore, using an auto-map.

Auto-maps in dungeons, we should realize, are different than hand-drawn maps, in that they are absolute. Hand-drawn maps are our own mental models-- a key difference.

For instance, auto-maps do not allow for the hidden space realization described in the earlier section. Likewise, in the process of making a hand-drawn map, we might miss drawing a passage, or make other mistakes such as connecting the wrong passage due to mis-estimating distances somewhere.

It's important to note that with a larger viewport, hand-drawn maps become less interesting, because it's more possible to understand the relationship between things when we can see both of them at once. In this case, creating a hand-drawn map has less utility, so it feels more tedious. In this case, an auto-map makes more sense because the benefit to the player (of either a mini-map or a hand drawn map) is relatively small but the cost to them (in terms of time and effort) is the same.

Aside: Possible Auto-Mapping Variations

I wonder about the value of an auto-mapping system that intentionally leaves certain details out or otherwise distorts reality somehow. Most auto-maps do leave out some details, but don't get the actual space wrong. So in such a system the player would need some way to understand that the auto-map isn't absolute.

One idea would be hand-drawn maps we find as we progress, pieced together, and that shows our position automatically but only within a certain range. The player could accept these are fallable since they were drawn by an in-game character; they represent this character's knowledge only, not the absolute knowledge of the game engine.

Very few games nowadays have small viewports, and almost all now have auto-maps. The only common genre I can think of with small viewports is "first person dungeon crawlers". I think Etrian Odyssey is one such game, and it did feature an in-game system where you hand-draw a map (note: not sure as I haven't played it.)

Narrow Viewport Size: Overworld, Towns

Back to Ultima VI, the narrow viewport also works well in the overworld, when we're in the wilderness. It creates a strong sense of exploration, when we don't know what's around the bend; likewise, traipsing from town to town ends up requiring us to remember signposts, forks in the road, or other scenery changes-- much like how we navigate the real world. It's very possible to get lost in the wilderness, which feels appropriate. (Drawing maps in the overworld isn't necessary because the game comes with an overworld map; more on that later.)

The small viewport works less well in towns, however. In short, it can be nearly as hard to get a good mental map of a town as it would be a dungeon, but since towns are friendly spaces, designed (for the most part) to navigate easily, it doesn't seem that making a hand-drawn map should be required. Since most players won't bother to draw a map for towns, they will find it relatively easy to get lost, not really being clear about where buildings are relative to each other (since you'll never see both of them at once) which is an annoyance.

In-Game vs. Absolute Knowledge

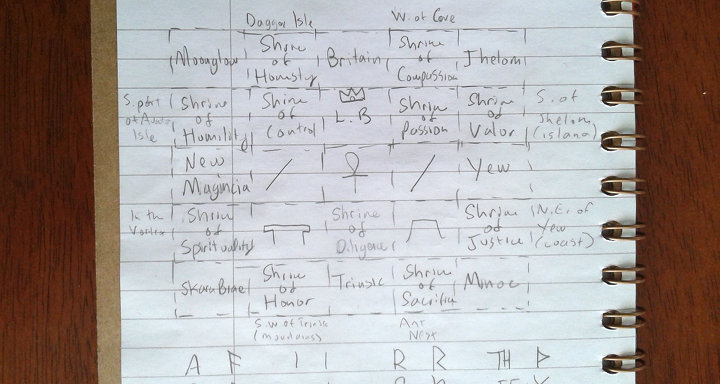

Ultima VI comes with a cloth map of the overworld, which shows the entire overworld in a lot of detail, and to correct proportions. It's a practical necessity, because of the sheer size of the overworld, and especially because of the relative position of certain islands that can only be reached by boat.

Without a map, it would be necessary to draw one, which would be incredibly tedious. Unlike dungeons, which are mostly corridors, the overworld is mostly open or semi-open spaces.

A branching corridor can be drawn in the wrong proportions and still be connected later, through the process of elimination, if we happen to double back on it. So it's possible to draw the underworld maps with only a rough estimate of space. And a map of corridors will capture the most useful information even if not to scale.

Out-of-proportion open spaces, on the other hand, will not connect in this way. We need to know the relative distance of points of interest, since the placement itself, in many cases, is the key information. So we could draw an overworld map in terms of roads, but capturing what lies between them would be far more difficult without some way to measure. This measuring would be very tedious.

At any rate, what makes the cloth map so interesting is that, while it shows almost all points of interest and is really bursting with detail, it still doesn't represent absolute information about the game. It's not a "game map", it's a map that would be used by characters in the game.

In this respect, it already is a hand-drawn map-- just one drawn by (supposed) in-game cartographers, who presumably have already completed the very tedious task of taking the required spatial measurements.

This fact is very useful-- it let's the designers provide a complete and trustworthy map, but on which certain key information is still absent.

One quest has the player traveling to the town of Yew to purchase a log. However, the town itself doesn't have anywhere we can purchase one. Instead, we need to ask the mayor about it. She tells us to head west in the forest, until we can't go any further, then north, and we'll come to the wood-cutter's hut.

The cloth map shows the town, the connecting roads, and the forest. It doesn't show the wood-cutter's hut. It's not done to intentionally mislead us; it's just something that wouldn't logically be on the map. Discovering this information through the pure-keyword system is very empowering.

This is a great device that's only available because the map represents in-game (as opposed to absolute) knowledge about the game. This approach could be more broadly applied to game design as long as the distinction was somehow made clear to the player.

Lack of Signposting, Dungeon Wall Shapes

Due (I imagine) to limited storage combined with a very large game world, maps are made from large-ish blocks (probably 8x8 tiles) pieced together. To avoid monotony, the designers created the blocks in interesting shapes. These blocks are used repeatedly; for instance, the bottom left-hand corner of rooms in dungeons often contains a small loop shape.

Unfortunately, these interesting shapes create some confusion because they are recognizable, but not distinct from one another. So the small bottom-left-hand-corner loop appears countless times, and we come to recognize it easily, but it's shape doesn't convey any useful information in terms of navigation; it's the same as if the room had a simple nondescript corner.

This problem shows itself on the overworld too, to a lesser extent:

This isn't a criticism, just a remark at how important and useful terrain signposting can be. If the wall-shapes were not subject to storage limitations they could have been used with more variety, to create a unique language for each dungeon or area and help the player orient themselves. This wouldn't (necessarily) eliminate the need to draw maps, but it would make drawing maps easier and probably more enjoyable since they would be less subject to distance estimation.

Overall though, even given the wall-shape (let alone tile set) limitations, the designers were able to create distinct areas through environmental storytelling, for instance spider webs in the spider cave, a giant table in the cyclops, or variously scattered dead bodies of explorers.

Fast Travel (Orb of the Moons)

I like to speculate above the development process of games, particularly with mechanics that stand out slightly and may have been added later. In the case of Ultima VI, I wonder if the Orb of the Moons was added later in development as an antidote to the extremely large world size.

The Orb of the Moons is an item that lets the player fast-travel to any of 22 locations throughout the world. These locations are available from the very start of the game; they don't need to be traveled to in order to unlock them. (Using the orb of the moons, you place it along a grid relative to where the player character stands; the placement on the grid determines the destination you will travel to)

The first quest-objective is to free the shrines from the gargoyles. This involves solving a puzzle in each town relating to each of the eight virtues to retrieve a rune (and mantra.) Then, to free the shrine you must travel to it, combat the gargoyles protecting it, use the rune, and speak the mantra.

The Orb of the Moons lets you fast travel to each of the shrines, putting you right next, and also to Lord British's castle (and other safe areas.) So, once we have the rune and mantra for each virtue, we can warp to the shrine, free it, and warp out; this avoids not only combating the gargoyles but also traveling to the shrines themselves.

While avoiding combat does happen to fit well into the narrative structure of the game, being able to use the Orb of the Moons in this way does feel a bit of an unusual "short cut". Additionally, each shrine contains a Moonstone that we get as a reward for freeing it. These Moonstones have their own teleporting capability, but one that seems vastly less useful than the Orb of the Moons (in fact, I'm not quite sure how they work.)

An even more major shortcut is using the Orb to travel to the gargoyle lands, which is (I think) only otherwise accessible through a deep trek into the dungeon Hythloth (a hell-like dungeon.)

Considering the way the "free the shrines from the gargoyles" quest is short-cut, along with the duplicate functionality to the Moonstones, it seems possible that the designers realized through testing that the world was too large, and that players would spend an inordinate amount of time traversing it, so they introduced the Orb of the Moons.

It's possible that the original intent was something more along the lines of (what is now) a traditional fast-travel structure, i.e., where once you travel to a place for the first time, you can easily return, perhaps using the Moonstones.

Note that neither fast-travel option would have been used in any game up the point that Ultima VI was released. In fact, at the point of release it was likely the largest game-world yet conceived (some have said maybe the first "open world" game in the modern sense of the word.)

At any rate, it's an effective and striking device since it amplifies the open-world nature of the game, by not only making all areas accessible from the start, but also making them easy to access from anywhere.

Party Control, Player-as-Spellcaster

Ultima VI is a party-based game with a designated player character protagonist. The player controls a number of party members, but is supposed to be represented in-game by one in particular, "The Avatar." The conceit here is that The Avatar is the player themselves, transported into the game.

Party members are not normally controlled directly, even in strategic combat situations. By default, party members act automatically, and the player only controls The Avatar. (This approach is common enough today, but would have been uncommon at the time Ultima VI was released.)

An interesting design choice was to make the player character be the only meaningful spellcaster. This is done by giving the player vastly more magic points than any of the other party members (in fact, recruitable spellcasters rare) and by making learning a spell a simple matter of purchasing it as a recipe from a mage.

This is a deliberate choice that I think compliments the rhythm of the combat sequences in the game.

If the party members were to use magic, the behaviour code would either have to make very good decisions about what spells to cast (so as to not frustrate the player) or be controlled manually (which works against the notion of only controlling The Avatar.)

In addition to requiring Magic Points, casting spells consumes special inventory items of several special types, called Reagents (these have evocative names such as Black Pearl, Blood Moss, and so on.) Managing Reagents (itself is an interesting mechanic also present in Ultima V, at least, and maybe earlier games) can be a slight burden. By effectively limiting spellcasting to The Avatar, it's much easier to keep Reagents organized and supplied. Hunting them down can be enjoyable, but overall this mechanic could easily become onerous e.g., if they had to be continually split between party members.

Final Notes

An after-the-fact disclaimer: As of the time of writing I'm not (nearly) finished the game; I might write a part II if I have other thoughts later on. It felt useful to write this essay now though, especially as it's rare for me (or anyone, really) to actually manage to complete a game like this. I actually can't remember if I managed to beat the game before, or whether I may have used item hacks to progress past a certain point (I won't this time, though.)

It's also important to keep in mind that the implications of game mechanical systems can be hard to predict; just because the flood-fill visibility works the way it does, doesn't mean the designers chose it for those reasons. Ultima VII (7) does away with both the flood-fill visibility and the pure-keyword system, decisions that have other benefits. For the most part here I was only trying to understand these systems in some detail, not weigh them against others.

Finally, it might feel strange to have read an essay this long and to have not touched on the game's actual themes (in particular "The Virtues", and the gargoyles' dilemma.) This wasn't a deliberate omission per-se, I just chose to focus on analyzing certain game-mechanical aspects.

At any rate, I hope these design notes will be useful to someone. If you have thoughts or suggestions please do drop me a note calvin@kittylambda.com or (better) @psysal. Thanks!

◀ Back